Known as a comparison microscope, the device consists of two microscopes connected by an optical bridge. Today, forensic scientists still use a type of microscope, developed and perfected by two of Poser’s colleagues in the 1920s, to examine crime-scene bullets or cartridge cases-the metal cylinders that hold the powder and bullets before they are fired. Poser’s analysis not only set Stielow free, it made history as one of the first examples of applying modern forensic techniques to identify firearms. Now, NIST researchers have developed a new algorithm that makes this matching more accurate, by dividing the markings on the deformed bullets into segments, and correlating those segments with the reference bullet. However, crime-scene bullets are often deformed from collisions, which can make direct comparison difficult. These microscopic marks are highly similar for bullets fired from the same gun, meaning they can be used for forensic comparison, matching bullets taken from a crime scene to a particular gun.

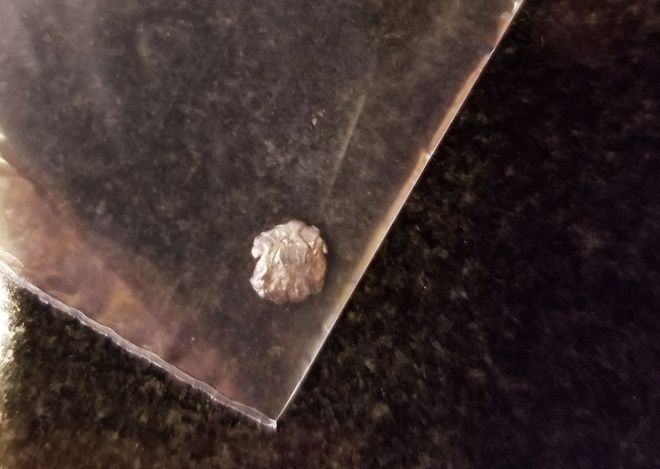

When a bullet is fired from a gun, the barrel leaves distinctive scratch marks on the surface of the bullet. Matching Crime-Scene Bullets Segment by Segment The bullets from the murder scene could not have been fired from Stielow’s gun, he declared. Even by eye, the markings on the two sets of bullets did not look similar but to make certain, optician Max Poser studied them under the microscope. A firearms expert from the New York City police department compared the bullets from the murder scene with those test-fired from Stielow’s gun. Just one week before Stielow was scheduled to be electrocuted on December 11, 1916, the Governor of New York called for a reinvestigation. Several people familiar with the case, including the deputy warden at Sing Sing, became convinced that Stielow was innocent and that his confession contained words that the farmhand, who was mentally challenged, could not have understood let alone uttered. He was sentenced to death in the electric chair and sent to Sing Sing prison to await execution. Although Hamilton never showed his evidence to the jury, declaring the findings were so technical they could only be discerned by an expert, Stielow was found guilty of murder in the first degree.

22 caliber revolver matched the nine scratch marks he had identified on the same caliber bullets at the crime scene. During Stielow’s trial, a self-proclaimed criminologist, Albert Hamilton, testified that the nine bumps he said he found inside the barrel of Stielow’s. He died a few hours later.Īfter finding that Stielow lied when he told investigators he did not own a gun, the police arrested him on Aug. Across the street, in the farmhouse where Stielow had recently begun work and where the dead woman had kept house, 70-year-old farmer Charles Phelps was found shot and unconscious. A woman clad only in a bloodied nightgown lay shot to death in the snow on the doorstep of an immigrant farmhand, Charles Stielow. On the morning of March 22, 1915, residents of the small town of West Shelby, New York, awoke to a horrific scene.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)